WHAT IS

MATH AND POLITICS TRIVIA

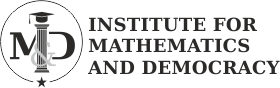

Under extremely hypothetical conditions, a candidate only needs 11 votes to win the presidency!

To see this, list the states according to the number of their electoral votes, starting with the highest (California). Add the electoral votes from the top until you get to 270. It turns out that this happens after 11 states. Now suppose only one person in each of those state votes, and they all vote for the same candidate. This candidate then gets 270 electoral votes and wins the election. In this instance, even if all of the remaining voting eligible people in the remaining 39 states (about 109,000,000 people) vote for an alternative candidate, the candidate with 11 votes would still win.

Though this scenario is highly unlikely, this exercise shows the weakness of the Electoral College. In fact, under more reasonable assumptions, a candidate could become the president by winning only about 23% of the votes. In U.S. history, there were 5 instances where the popular vote did not match the results from the electoral election (1824, 1876, 1888, 2000, 2016).

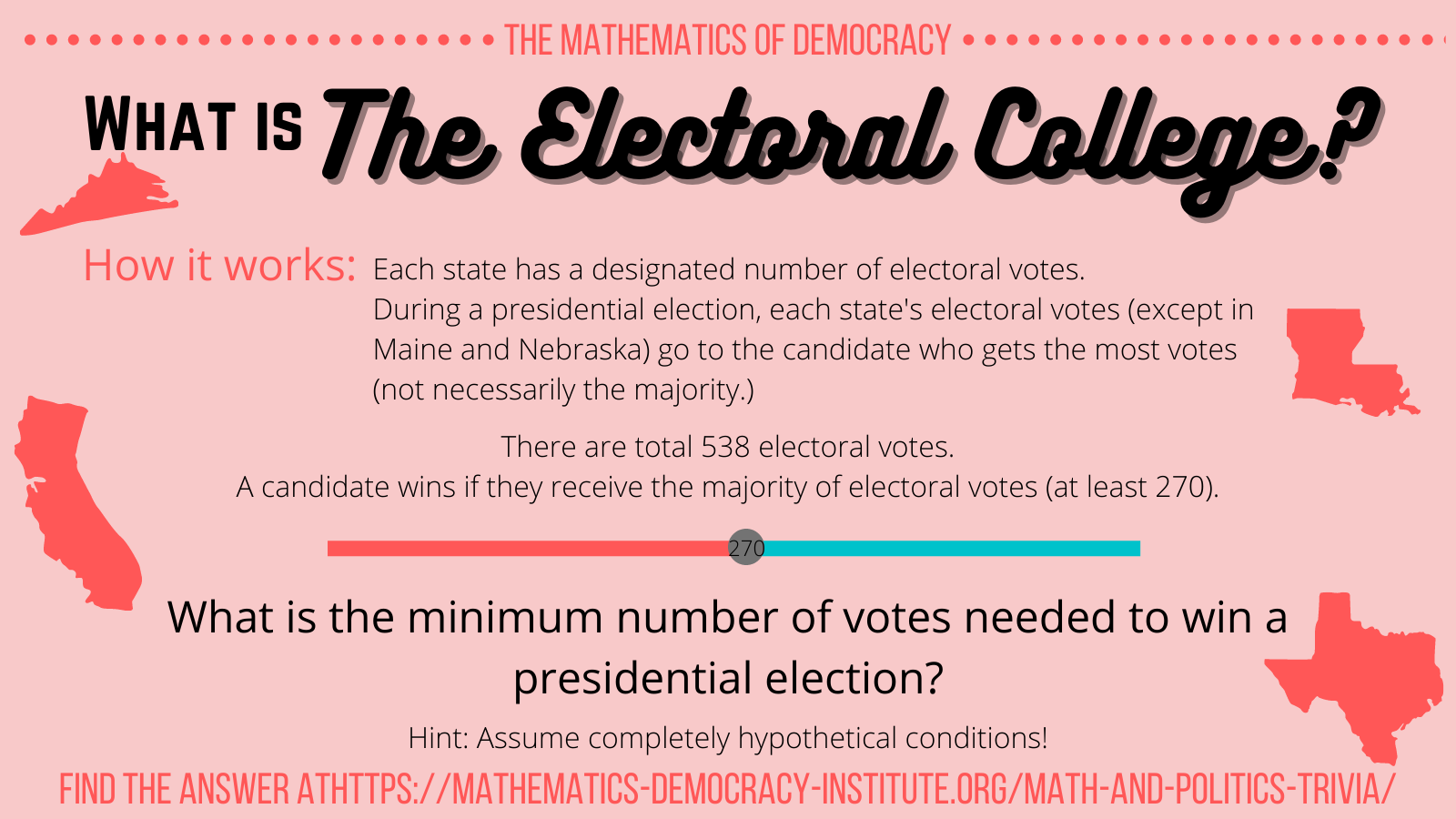

In a presidential election, voters do not directly choose the president; instead, statewide election results are interpreted through a state’s allocation of its electoral votes. The portion of a state’s electoral votes based on that state’s representation in the House is approximately proportional to the state’s population (see earlier apportionment trivia to learn more.) Therefore, votes from large vs small states have the same effect on the Electoral College for this portion of electoral votes. However, every state has exactly two senators so each state gets two additional electoral votes no matter its population. In a large state that already has many electoral votes, these extra two may not particularly affect the ratio of electoral votes per person. However, in a small state, these votes “matter more”: states with small populations have more electoral votes per capita, a phenomenon called the “+2 effect.” For example, the number of people per electoral college vote in California is 735,000, while this number is 192,000 in Wyoming. This may mean that a vote from a small state has a larger direct effect on the Electoral College, and thus the outcome of the election, than a vote from a larger state.

The “+2 effect” means that individual votes in different states carry different weights. However, from the perspective of states as a whole, the Banzhaf power index suggests that bigger states have more power in deciding the presidential race. See our previous quantification of power trivia for more details. Thus, though the +2 effect may be countered by the power of large states, it is still a symptom of the weakness of the Electoral College.

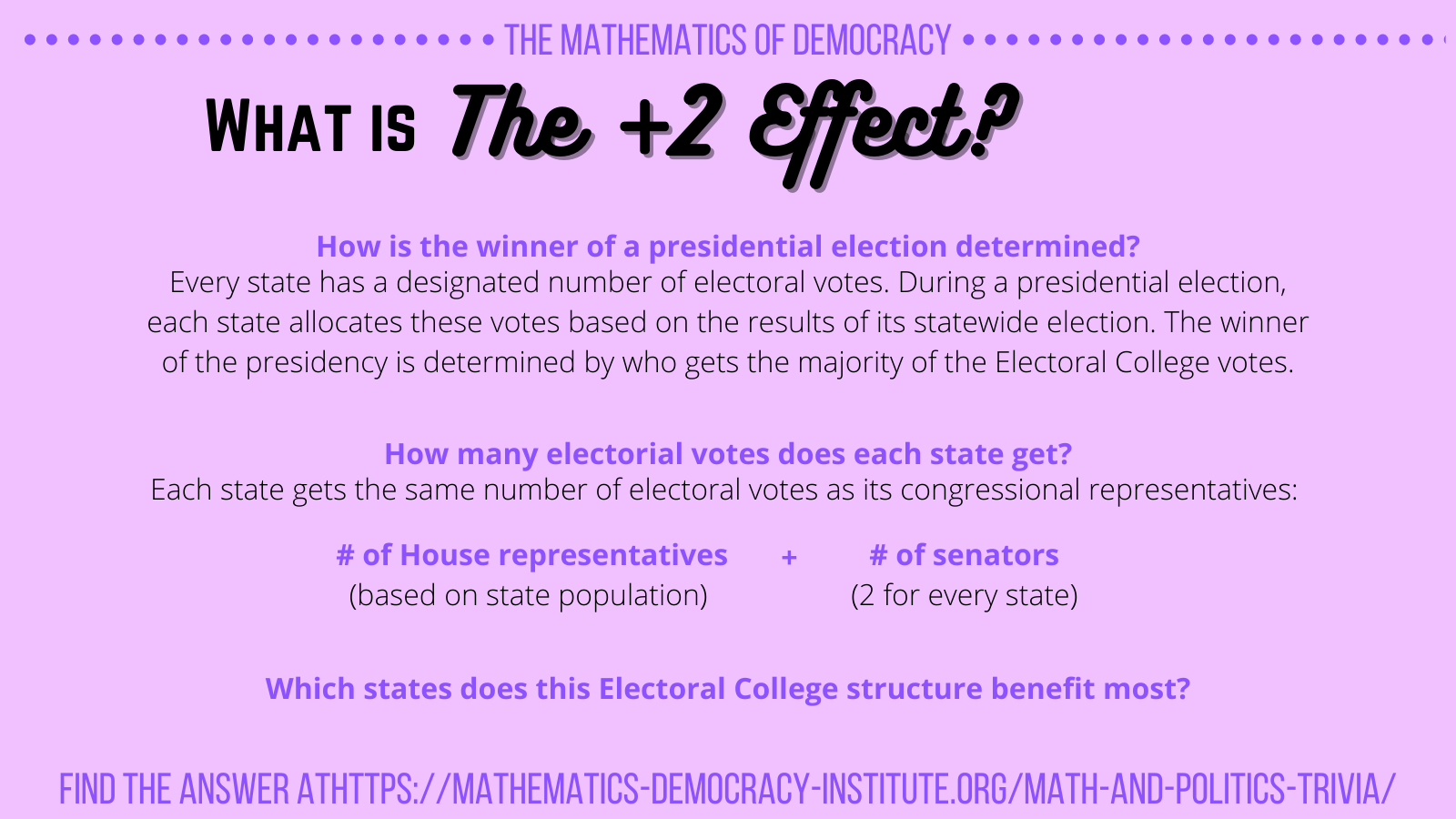

There are various ways to do this. Let’s assume all voters participate in the election. One solution is:

- A little more than half the voters in Massachusetts, say 3,460,000, vote for A.

- Same in Wyoming, with, say, 293,000 votes for A.

- Everyone else votes for B, so B gets 11,182,000 votes

So A carries 14 electoral votes and wins the election with 3,753,000 votes. B gets far more votes – 11,182,000 – but only 13 electoral votes!

(The key is that Wyoming tips the electoral vote to A with relatively few votes.)

Now suppose not everyone is necessarily voting (in fact, turnout for presidential elections is usually about 55%). Given this same scenario, what is the minimum number of votes that could secure a win for a candidate? We will look at an extreme example to answer this question. Suppose only one voter each turns out in Massachusetts and Wyoming and votes for A. Then A wins those states and gets 14 electoral votes. (If everyone votes for B in the other two states, this would mean that A won the election with only 0.0000268% of the popular vote!)

Though this scenario is simplistic, there are several instances in American history where the president did not win the popular vote:

- In 1824, John Quincy Adams was elected president though Andrew Jackson won 10.5% more votes.

- In 1876, Rutherford B. Hayes won despite Samuel J. Tilden winning 50.9% of the votes.

- In 1888, Benjamin Harrison was elected over Grover Cleveland, though Cleveland won 0.8% more votes.

- In 2000, George Bush became president, while Al Gore conceded even after winning 0.5% more votes.

- Most recently, in 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency with 46.1% of the vote versus Hillary Clinton’s 48.2%.

This means that it has happened almost 9% of the time in presidential elections!

Why does this discrepancy between the popular vote and the electoral vote happen? As illustrated with our example, the crude winner-take-all system is to blame. The winer of the popular vote carries all the electoral votes in each state, regardless of their margin of win. A candidate could barely eke out a majority of the popular vote or win by a landslide, but in the end, the electoral vote allocation does not see this difference. The +2 Effect also makes a difference (see the post on this in the Electoral College trivia section).

From previous trivia, we know that the Electoral College is flawed, but what can we do to change it? Abolishing it entirely in favor of the popular vote is the most obvious solution. However, this would be difficult to accomplish since it would require a Constitutional amendment with 2/3 of House and Senate voting for it and 3/4 of the states ratifying it. This means that many small states would have to sign on, but they would likely not want to give up the influence their electoral votes give them.

To bypass this difficult procedure, the other solutions have been proposed. First, in order to add enough votes so that each represents the same number of people, a substantial amount of electoral votes need to be added. The smallest per-population vote is Wyoming’s (192,000), so this would have to be the population for every vote. This would resolve the issue of voters in some states having more influence on presidential elections than in others. It would also result in some 1,700 electoral votes but expanding the House to accommodate this number would likely be very unpopular as voters are generally opposed to increasing the size of the government.

The next possibility is to apportion the electoral votes according to the percentages of the popular vote in each state. In this case, if a candidate gets 60% of the popular vote, she would get 60% percent of the electoral votes (rounded somehow). This is fine since the states are not bound to use the winner-take-all system. Rounding the percentage of votes may get tricky, but this would better reflect the popular vote than giving all the votes to one candidate.

Another potential solution is to assign one electoral vote to each congressional district. This works out because the amount of electoral votes per state is directly determined by the number of a state’s seats in the House (and thus congressional districts). The two extra senate votes could go to the overall majority winner candidate in the state. Not only is this solution feasible, but it is already implemented in Maine and Nebraska. The “+2” effect of the Senate votes would still introduce an imbalance in the influence on the Electoral College voters in different states would have.

Finally, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) could be a solution that gets around the Electoral College in an elegant way. It is a coalition of states which have agreed to allocate all their electoral votes according to the national majority winning candidate. This plan would only work if enough states joined so that the total number of the votes they carried exceeded 270. See our previous trivia to learn more about the NPVIC.

The chaos of the 1800 election had many fearing that the United States would enter into civil war. So after the election was settled and Jeffrson became president, Congress adopted new rules concerning potential ties in the electoral process. Previously, electors cast two ballots for president and the candidate with the highest total would become president. The one with the second highest vote tally would become vice president. Even though Burr ran as Jefferson’s vice president, the Democratic-Republican electors submitted one ballot for each of them, resulting in the tie. In response, the 12th amendment was ratified in 1804, now requiring electors to cast one ballot for president and one for vice president in order to prevent a tie between two candidates of the same party. This amendment also stated that, in the event of a tie, only the three candidates with the most electoral votes are voted on by the newly elected Congress. Just as in 1800, the House of Representatives would vote for the president, with each state receiving one vote. With the current 50 states, the majority of 26 votes would be needed to win, while each senator would vote for vice president, again with a majority of 51 votes needed to win. However, to prevent the tedious 36 rounds of voting that occured in 1800, there is now a deadline: If the House cannot reach a majority decision by May 4th, the newly elected Vice President becomes acting president.

The 12th amendment is one of the only examples of an attempt to modify the Electoral College that actually succeeded. For example, it changed the outcome of the 1824 election, when four candidates received significant electoral votes. Though Jackson received both the plurality of the popular vote and the electoral vote, Congress chose a different candidate, John Quincy Adams. According to Jackson, this was a result of a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and the Speaker of the House at the time. The final tie in American presidential elections to date was for Vice President in 1836, but this was resolved in the Senate without too much trouble.

It is important to note that a tie in the Electoral College does not necessarily mean that the candidates received the same amount of votes. Most states, with the exception of Maine and Nebraska, allocate all of their electoral votes to the candidate who won the plurality of votes in their individual statewide election. Thus, it is possible for a candidate to win the popular vote but tie in the Electoral College. Additionally, only 33 states have faithless elector laws requiring electors to vote in accordance with the results of their statewide election. In fact, in 2016 there were 7 faithless electors who voted against the winning candidate in their state. So even if two candidates tie in both the popular vote and with an even split of electoral votes, it would be possible for one elector to switch their vote and swing the entire election. This highlights one of many structural issues in the Electoral College. Stay tuned for more trivia about how ties are broken in other American elections.